Sometimes, a brief moment is enough to realize the true role of light. A hand resting in warm light. A room intentionally dimmed in the evening. A moment in which nothing presses and nothing demands. It is precisely in these situations that light is not only seen, but physically felt.

Light becomes tangible

Light accompanies us every day, usually without our awareness. Only when it is absent or excessive does it come into our consciousness. Research has long shown, however, that light is far more than a visual design element. It has biological effects, influences our well-being, and regulates key processes in the human body.

Light is not just something we see. It is something we feel. Good light does not impose itself. It supports, creates a sense of safety, calm, and depth. This is exactly where well-being begins.

The effect of light on our internal clock

One of the most important functions of light is its effect on our internal clock. Light is among the strongest time cues for humans and regulates the so-called circadian rhythm—the natural cycle between activity and rest. This connection is scientifically proven, measurable, and a central element of modern chronobiology. Light influences concentration, alertness, relaxation, and recovery—often without us even noticing it.

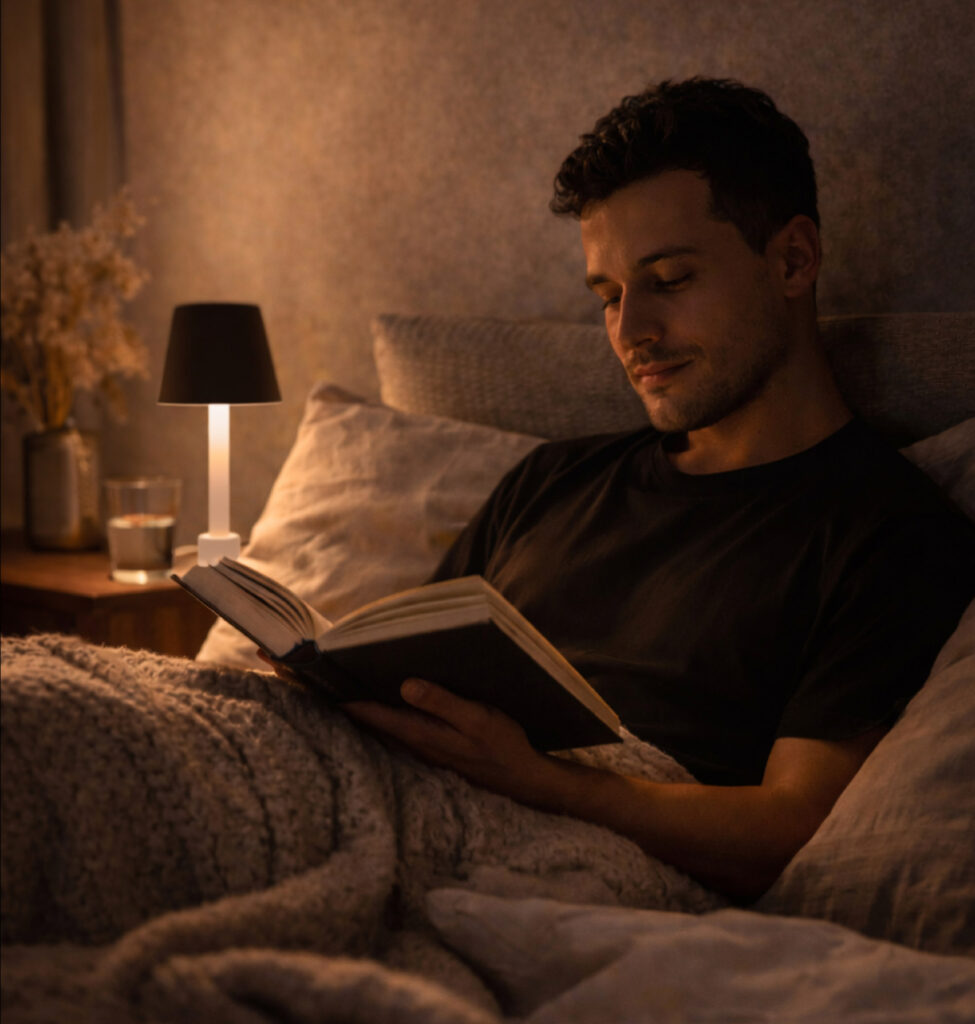

Light does not act in an abstract or theoretical way. Its effects unfold in everyday life, in the very situations we experience daily: reading in the evening, arriving home after a long day, or in moments of quiet.

Light color – what calm feels like

In the evening, the body’s needs change. Activation takes a back seat, and transitions become more important. Warm-looking light with reduced blue content supports this natural process. Studies show that short-wavelength, blue-rich light, especially in the evening, can inhibit melatonin production. Warmer light colors are therefore perceived as more pleasant, calming, and less disruptive.

This effect is neither an aesthetic trend nor a matter of taste. It is based on biological processes. When light flows softly over surfaces, when faces are not harshly defined, and spaces retain depth, calm does not arise by chance. It is deliberately created.

Light levels – between tension and ease

In addition to light color, the amount of light also plays a crucial role. Too much light can create inner restlessness, while too little light feels tiring and makes orientation difficult. Research and standards therefore recommend clear distinctions between day and evening: sufficiently bright light during the day and significantly reduced brightness in the evening hours.

Dimmability, in this context, is not a comfort feature, but a fundamental function of good lighting. Light should be allowed to step back. In well-designed lighting scenes, nothing is overexposed, nothing forces itself into the foreground. The light is present, yet it is allowed to grow quieter.

Adaptation instead of rigidity

Good light is not static. It follows the moment and adapts to the situation— to the time of day, the activity, and the mood. People should not have to adapt to the light; the light should adapt to life. Whether reading, sitting, breathing, or arriving home, light becomes part of the moment without being its center. It supports rather than dominates.

Glare & light distribution

When seeing becomes tiring glare is not a matter of perception, but a physiological phenomenon. Stray light in the eye reduces contrast and makes seeing tiring, especially as we age. For this reason, standards and studies place great importance on shielded light sources, smooth brightness transitions, and controlled light distribution.

Light can be visible, but it should not be intrusive. Atmosphere does not arise by chance, nor through decoration alone. It is created by light—through deliberate transitions, through scenes, and through reduction.

Feel the Light.